5 Questions to Kelly Richardson

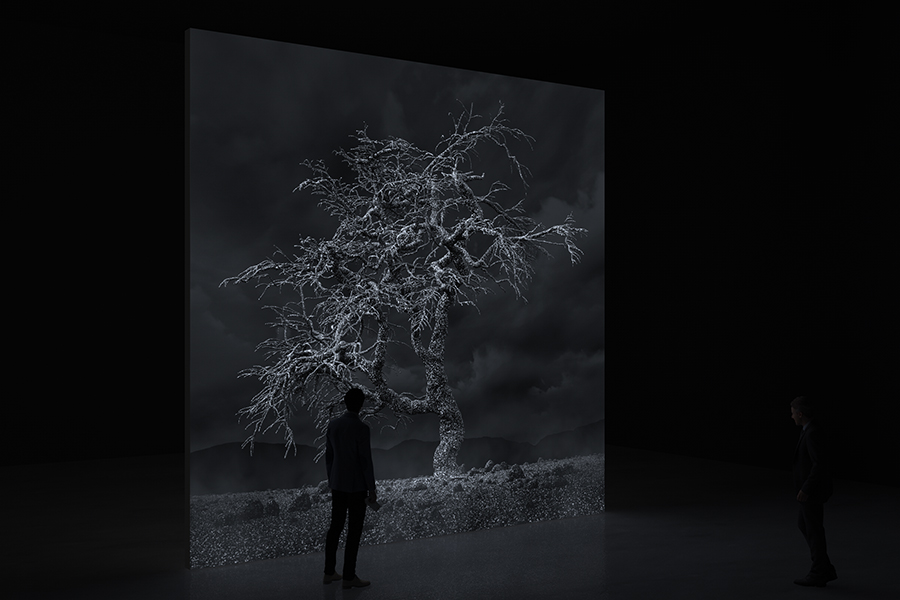

In the Marta exhibition “Deceptive Images”, the relationship between artefact and document becomes blurred when we enter into the constructed world of Kelly Richardson’s video work. It blurs – backed by sound – the separating line between reality and fiction. In this interview, the artist answers our questions.

You first studied painting and drawing before you turned to media art. What was the reason for the change?

Following my undergraduate degree, which focused on drawing and painting, I started to ask why I was restricting myself to those mediums. I enjoyed painting, but something was missing. Therefore, I shifted my focus to leading with ideas rather than medium and gave myself the freedom to explore without restriction. Video entered my practice at that point, along with photography, sculpture and installation. Over a few years of exploring, video naturally took over as the favoured medium. I found that what I could accomplish in terms of effect on the viewer could not be replicated with any other media.

Having said that, I didn’t really leave painting behind, as such. I take a very painterly approach to working with the moving image in that no pixel is left untouched. The images are constructed with careful consideration of not just composition, but colour, tint, tone and shade. Each of the videos that I produce require hundreds of layers of adjustments to “paint” the moving image.

Landscape plays a central role in your oeuvre. It is also a classical genre in painting and photography. Are there concrete historical models that have a special meaning for you?

Much of my work produced from 2006 onwards came out of an interest in the Apocalyptic Sublime, a sub-genre of Romanticism where artists, poets and writers shared a preoccupation with notions of the apocalypse in the 18th and 19th centuries. There is a great deal of speculation as to what the influences of the genre were exactly. However, a significant one was the birth of the Industrial Revolution, which played heavily on the minds and hearts of creative practitioners at the time – imagining what the fallout might be through such a radical shift in our relationship to the planet. Roughly 200 years on, we are now facing severe consequences from relentless industrialisation.

I grew up in a city where environmental issues were at the forefront of thought and action. I felt anxieties about where we were heading as a species at a very young age. When I experienced the landscape paintings of John Martin in particular (a painter of the Apocalyptic Sublime) while living in north east England, my interests, anxieties and creative practice began to align.

You often work with digital software from the film and games industry. What freedoms does this give you as an artist, and to what extent does this prescribe a certain aesthetic and range of motifs?

The capabilities of digital software allow me to create what I’m imagining with incredible control. Early in my digital media practice, limitations with software on the prosumer level certainly had an impact on the aesthetics of the work. That is true for the film industry as well. Advancements in technology have been substantial since that time, so any aesthetic impact would be slight from my perspective, if any at all. I’m not prescribed any motifs as all digitally created elements in my work are constructed in my studio.

How important is sound in your work?

In the film industry, they say that sound impacts about 60% of our experience as viewers. As a visual person, I found that hard to believe when I was first made aware of it, but have found that to be true. A fun test of that theory is to watch one part of a film with the sound off and then the other one with your eyes closed and the sound on.

Sound has an enormous impact on our ability to immerse ourselves within the moving image, which is so important in the work that I make. I want viewers to imagine themselves in my landscapes, and in doing so, really feel them through both the head and the heart. It allows me to situate viewers and at the same time, amplify a particular feeling that I want them to experience.

Your works are often based on scientific findings or are even created in collaboration with scientists. What can art learn from science and science from art?

Through science, creative practice is informed. Through art, creative thinking reveals truths.